Teaching College Prep...

As the principal for a college preparatory high school program specifically geared for students with learning differences, I can say that many students enter college with a number of wildly preconceived notions and myths that statistics and experiences belie. Some of the prevailing myths being generated by students, parents, and the media include:

- The partying goes on all the time on and around campus, leading many of the current class of seniors to believe that college represents a bacchanalian (e.g., "Animal House") hiatus between childhood and the real world. This prevailing view of college life is historically passed on when former students are home from college for the holidays and return to visit their former high school teachers and friends, often regaling them with the wildest of their college out-of-class expereinces and, in many cases, fantasies.

- Based upon the "word on the street" experiences of college students, rumors persist that a large number of the social science classes they will have to take at some point are--with some justification--often viewed as "jock" (easy) courses because a substantial number of athletes often major in that area while attending college. The antithesis of these courses are the dreaded math and science classes.

- Another common myth is that community or junior college instructors demand far less than instructors at four-year institutions. Related to this is the belief that students will either not have to or, if they do, write fewer papers if they attend two-year institutions.

- Yet a fourth myth is that students will often be asked to read only one textbook, as can happen in high school, and that instructors just "teach the textbook."

- Finally, it is thought that college students, especially those at large universities, will be able to pass through lower-division courses as anonymous bytes on a diskette, just faces in a cavernous lecture hall. Some people go so far as to believe that attendance is of little importance or consequence.

Such are the expectations of what one will face in college among a sizeable portion of our high school population. One of the greatest challenges confronting a secondary-school teacher is to prepare students for college in realistic terms, since far more colleges, two-year as well as four-year, demand much more than these myths suggest. What studies on this topic have shown is that a strong majority of college instructors expect students to read beyond a single textbook, to write papers (plural), and to take essay exams--all of which suggests some points as to how high school teachers can prepare students for facing college level classes.

Based on a number of studies, there often exists some variance between two-and four-year institutions in that two-year colleges often require more per-course examinations and fewer textbooks than four-year institutions. As far as any other differences, studies for both types of colleges suggest that core academic courses will be challenging.

As a teacher and administrator, I know how challenging it is to prepare any but the most naturally gifted students for college. Various states (Texas is one) make this all the more difficult by requiring standardized bench mark and exit-level testing of a simplistic nature, forcing teachers to spend too much time on mechanical multiple-choice exams instead of writing document-based questions as is more common in Advanced Placement and college level classes. Then, too, we principals often demand that teachers try a lot of new time-consuming techniques that don't necessarily help prepare students effectively and work with classrooms of students whose abilities range up and down the scale of educational background, academic skills, and post-high school aspirations.

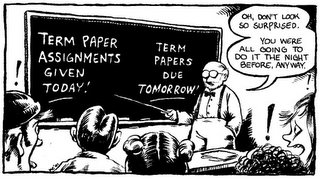

However, experiences with our students confirm what many of us have known all along--high school students expecting to go on to higher education must, above all, be taught to read and write effectively. As a history teacher, I required students to work on a family tree and write a book review, take essay type exams that required synthesis of thought and clarity in written explanation, and to work with me as we trudged step-by-step through the researching, drafting, and revising of term papers. Thus they learned to interpret historical evidence and experienced a variety of history writing beyond their textbooks. Not every high school student is a college-bound "scholar." But teaching with regular quizzes, essay examinations, and document-based papers, combined with the Socratic discussion method, can only better prepare students of diverse backgrounds and capabilities for college. Education is a disciplining process and, as educators, we owe it to ourselves to help realisitcally prepare our students for whatever future successes they are capable of achieving.